What is grey literature?

Grey literature covers all materials that are not published in books or journals. Examples are PhD theses, conference abstracts, working papers and technical reports. Because such materials are not published conventionally, they lack indexing in major electronic databases such as Medline. For this reason, finding grey literature for your systematic review is typically more difficult than finding published studies.

Why should I search grey literature for my systematic review?

Cochrane recommends searching in grey literature sources, to reduce the risk of missing studies and to find as many studies as possible. Furthermore, it is known that published studies on average show larger effects than unpublished studies. Missing such studies could influence the results and the conclusion of a review. See also: MECIR standard C28.

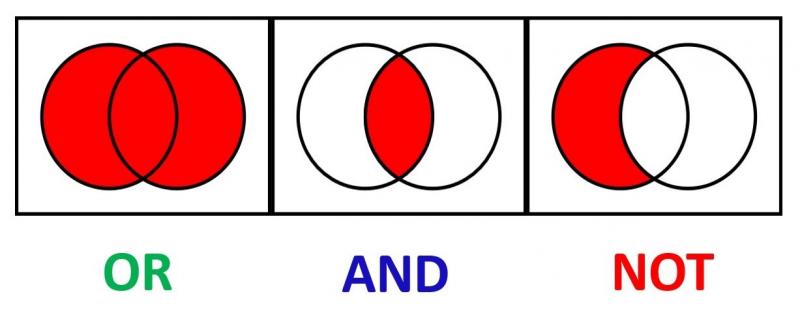

What are Boolean operators?

Boolean operators are words that can be used to develop a (systematic) search strategy. These words connect multiple search terms in order to find more specific or broader content. The most well known are AND, OR and NOT.

The search ‘exercise OR knee osteoarthritis’ results in records that report on either exercise or osteoarthritis, thus more broad results.

The search ‘exercise AND knee osteoarthritis’ results in records that report on both exercise and osteoarthritis, thus more specific results.

The search ‘exercise NOT knee osteoarthritis’ excludes records on knee osteoarthritis. Such search results thus in records on exercise but not those on knee osteoarthritis.

What are proximity operators?

Proximity operators are terms that help you search for two words that should be combined in order to get more specific results. Separate databases may have separate proximity operators. The following are examples from the Cochrane database.

The term ‘near’. Searching for ‘prostate near cancer’ gives all reviews that have prostate and cancer with maximum 6 words in between. The order does not matter, thus both ‘cancer of the prostate’ and ‘prostate and bowel cancer’ will be retrieved. It is possible to specify the number of words in between using ‘near/x’ where x represents the number of words.

The term ‘next’. Using this term, you will find reviews that have the first word before the second one. Searching for ‘prostate next cancer’ gives only reviews that have prostate before cancer.

Pubmed does not offer these proximity operators.

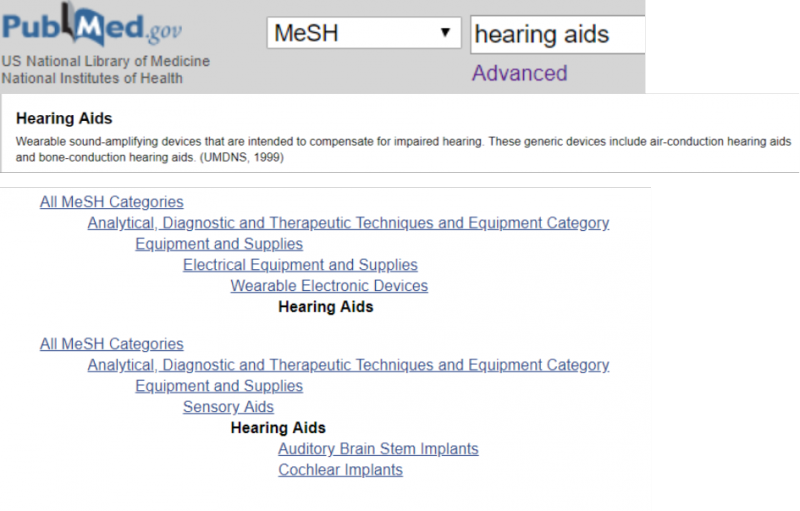

What are index terms?

Index terms are standardized terms which databases assign to new articles. You can search many databases, including MEDLINE, Cochrane and Embase, using index terms. The most well-known are MeSH terms, short for Medical Subject Headings, used in MEDLINE and Cochrane. In Embase, Emtree terms are used.

Index terms are useful if you search for studies for a systematic review, because they allow you to retrieve articles using different terms to describe the same topic.

However, a search that consists only of index terms is unlikely to capture all relevant articles, as the indexing methods of different databases are not standardized. In addition, the most recent articles may not be indexed yet.

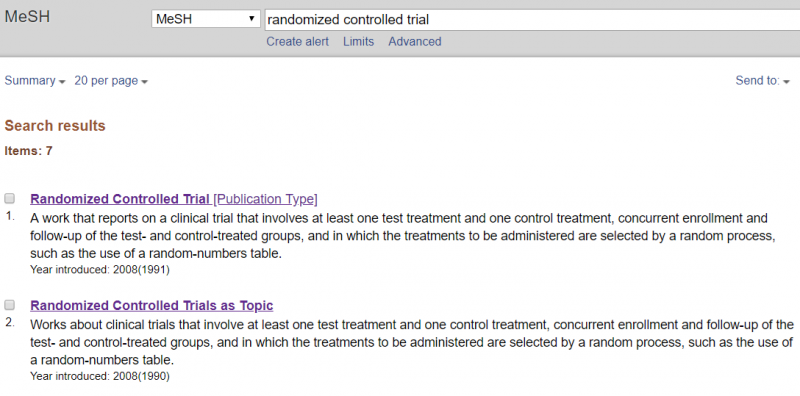

When to use publication type terms in your search?

Publication type is one of the different categories of the MeSH database. These terms are used to distinguish reports of, for example, randomized trials from reports about randomized trials. To index a report describing results of a randomized controlled trial, the publication type term Randomized Controlled Trial is used. To index reports about randomized controlled trials, the MeSH term Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic is used. This principle also applies to indexing terms for other study types.

How to minimize bias in your search?

Systematic reviews require an extensive search in order to identify as many relevant studies as possible. This reduces the risk of selection bias in the traced studies. The extensive search is one of the characteristics that distinguishes systematic from narrative reviews and increases the chance of reliable results.

To minimize the risk of bias in your search, Cochrane recommends to search in multiple databases; at least in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), complemented by Medline and Embase (if not already covered by the above-mentioned register). Cochrane further recommends searching trial registers and checking reference lists of relevant studies and systematic reviews. In addition, depending on the topic and possibilities, it may be appropriate to search for grey literature, contact other researchers, search other (national, regional or topic-specific) databases or screen reference lists of other reviews on related topics.

See also MECIR standards C24-38.

What are citation indexes?

Citation indexes are databases of published papers with links to other papers citing the former. Examples include Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar.

For systematic review purposes, you can search citation indexes as source database. Furthermore, using the links you can find new possibly relevant studies in two ways. To do so, you start with a study that is already included in your systematic review. Using the citation indexes, you can check (older) studies cited by your included study on the one hand and (more recent) studies citing your included study on the other hand. Citation checking is a useful searching method in addition to searching literature databases.

What is Scopus and Web of Science?

Scopus is a citation index (see above). It contains both abstracts of studies and citations to and from papers. Scopus focuses on social medicine, but also has articles on medicine.

Web of Science is the internet database of Science Citation Index, previously known as ‘Web of Knowledge’. This collection of scientific databases focuses on high-impact and English literature in science and technology.

Another citation index, Google Scholar, is strong in non-journal types of information.

Differences between the databases are for example related to the coverage of disciplines, international and non-English studies and other types of literature, such as reports and dissertations. The library of the Iowa State University made a comparison between the databases.

Wondering which database you should search for your systematic review? There is no simple answer to this question. It depends on your topic.

What is the difference between Medline/PubMed and Embase?

Medline is a database of biomedical and life sciences journal articles issued by the US National Library of Medicine. The database focuses on healthcare professionals including researchers, practitioners, educators, administrators and students. Pubmed is the search engine for Medline. It offers free access, whereas for OVID, the other search engine for Medline, you need a subscription.

Embase is a European database of biomedical journals and conference abstracts issued by Elsevier. It is strong on pharmacology, including journals on drug research, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, pharmacy and toxicology. The index system of Embase, EMTREE, is also more sensitive to identify articles on pharmacological topics.

What is Cinahl, PsycINFO and PsycNet?

Cinahl and PsycINFO are topic-specific journal databases. To search these databases, you need a subscription.

Cinahl is strong on topics related to nursing and allied health professions including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, nutrition and dietetics.

PsycInfo is strong on psychological topics, more specifically behavioral and social sciences. PsycNet is a platform to search PsycINFO, developed by the American Psychological Association (APA). It also contains other information sources such as books and videos.

Why should I search multiple databases?

To increase the quality of your systematic review, you should search multiple databases. As explained in the previous FASRs, there are differences between databases, for example in topics, and thus journals and possible other sources they cover, and in the way they index and cite their papers. Searching various databases increases the chance of finding more relevant studies.

The importance of this is illustrated by the so-called MECIR standards on how to write a Cochrane review. They state that “searches for studies should be as extensive as possible in order to reduce the risk of publication bias and to identify as much relevant evidence as possible”. See also MECIR standards C24-38.

Any other suggestions to improve the quality of my search strategy?

The search for a systematic review does not have to be performed by two persons separately. Such duplication is recommended for other steps, for example screening studies for eligibility or assessing risk of bias.

However, it is useful to ask a librarian or information specialist with specific expertise in systematic reviews to peer review your search strategy. Peer review may identify search errors. In addition, the librarian may have suggestions for the selection of search terms, which may lead to finding additional studies. The PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) statement provides guidance on this.

What does a good study selection checklist look like?

A good study selection checklist describes criteria for all important elements of the research question. These criteria help reviewers to determine whether a study is included or excluded from the review. Important elements for intervention reviews are the description of:

- the patient population;

- the intervention;

- the control.

The checklist describes each criterion in a clear and explicit way, thus assisting two independent reviewers to make the same decision on a potentially relevant study. Such checklist is part of the protocol and should be ready before the start of the review. It also reports whether the outcome is part of the selection process or not, as this is not always the case. See also MECIR standards: C5-13.

Do we really need to work in parallel to conduct a good systematic review, and during which steps is this most important?

Preparing and performing a systematic review takes many decisions. Doing parts of the review in duplicate reduces the risk of making mistakes. It also reduces the possibility that the beliefs of one reviewer affect the decisions, which may cause bias. Working in parallel increases the quality of your systematic review.

For Cochrane reviews, working in parallel is mandatory when making inclusion decisions for studies, when extracting outcome data and when assessing risk of bias. It is highly desirable during extracting study characteristics (MECIR standards: C39, C45, C46, C53).

Do I exclude studies that do not report any relevant outcomes from my systematic review?

Studies that report no relevant outcomes should not be excluded from systematic reviews (see also MECIR standard C8). If a study fails to report outcomes, this does not mean that the study did not measure these outcomes. Information on other outcomes may be available from the authors.

This has to do with outcome reporting bias, i.e. bias that arises because statistically significant results are more likely to be reported, whereas this is less likely for statistically non-significant results. Outcome reporting bias is an important threat to the validity of systematic reviews.